Welcome, Hoş Geldiniz: Thank you everybody for coming.

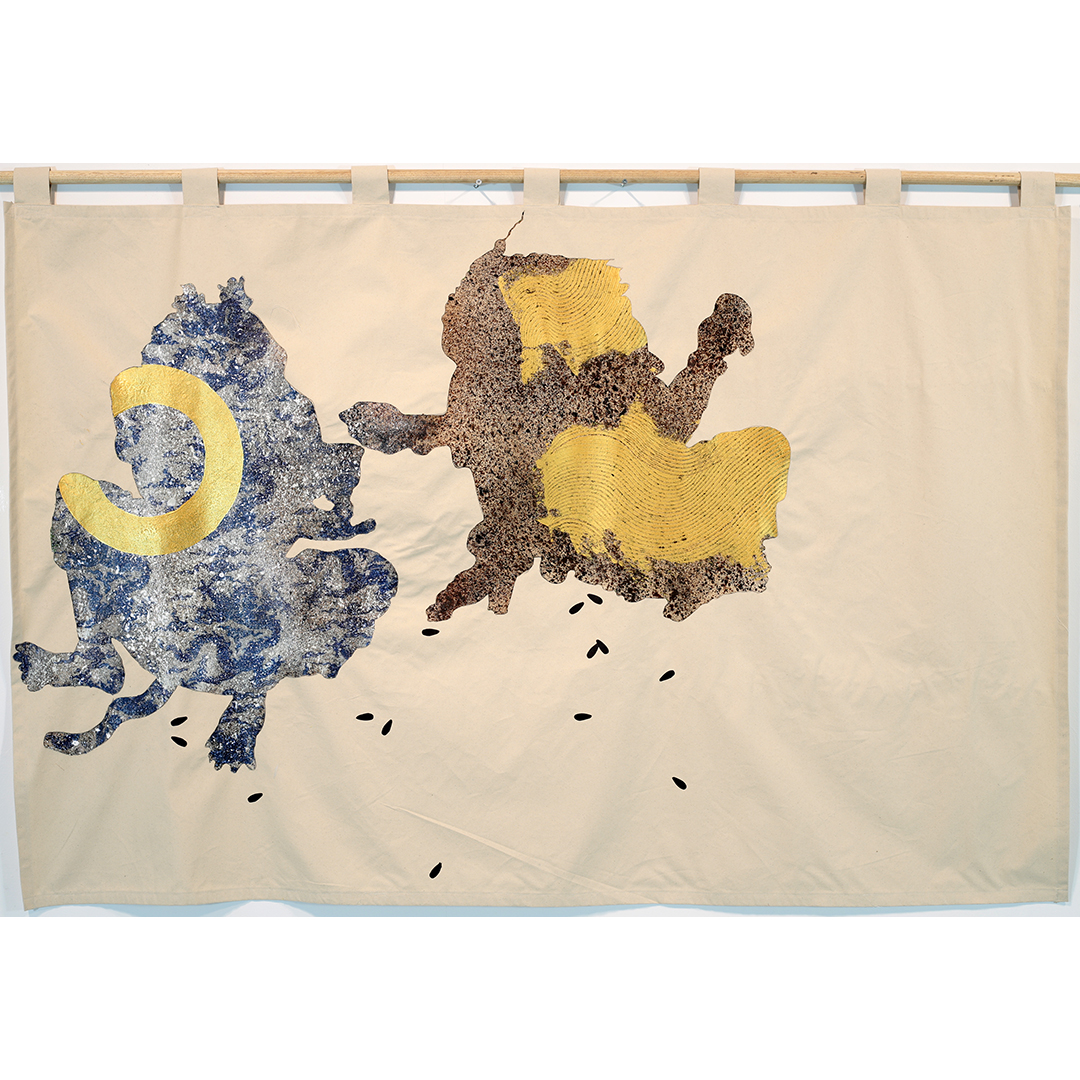

Before I start talking about Siyah Kalem, my life in Istanbul, and all the stories around this exhibition. I wanted to first get into the physicality of the work.

The actual making.

Because, even though the work seems so much about narrative, what’s actually happening is just as importantly a conversation about painting and visual language.

It’s about my own engagement and interpretation of the physical world.

It’s about decoding and re-presenting the surfaces and textures of things around me.

And, it’s about finding, and making, the ‘mark-making’ tools I needed. As well as developing the techniques to use them.

The figures themselves, at their very fundamental state, are often just emptied out vessels, sort of reversed shadow puppets, into which something more physical, about the act of painting, has been enacted.

As some of you already know, especially those who follow me on Instagram, I have already made and exhibited a smaller version of this work in Istanbul.

It was there, on residency, working in the city with the subject matter at my fingertips, that much of these processes where developed.

Originally, these were made on a table-top and the scale of the marks was dictated by the tools I employed, which were themselves dictated by the scale of the work.

So, when it came to say, the splattering, I used an old toothbrush. The lines on the surfaces were made with a scraper and a comb I found in the street. Other marks were made using sponges and bits of string dipped in paint.

Here in Sheffield, making this work, all those processes had to be scaled-up and needed new tools, some of which I had to make. For example, A toothbrush became a scrubbing brush, and a piece of string became a length of rope.

I’ve actually brought the stamp I made for the gold rings for you to see, the gold rings are a symbolic motif I developed from my observation of Siyah Kalem’s characters and their own reference to wealth and status symbolism. Interestingly, the tray I used as a palette for this tool was a Tepsi, which is a circular Turkish baking tray.

Equally, the act of making itself became highly physical with the work so big, it often had to be laid on my studio floor and me crawling all over it or worked on like a scroll.

The swirling surface, which was made using a tilers spreader I bought in Istanbul, is not just evolved from the beautiful swirling skins and furs in the original Siyah Kalem works, but also from running my hands along the textured marble walls of the apartments around the area where I live in Istanbul. I actually made a sample, it’s in the corner for people to touch, I encourage you to do so.

I guess what I’m saying is, that the pictorial in this work is actually a collage of abstract marks, processes, and colours, appropriated from the texture of the city around me as well as my deconstruction of Siyah Kalem’s own works.

So, as you read the narrative of the work, I ask you to consider the painting itself. Because there’s much within the surface of the work that is a reflection of the physicality of the place from where they came.

Which is Istanbul and 14th century Persia.

I’d now like to chat here about Siyah Kalem. I know I’ve mentioned him a few times and that many of you won’t know who he was, so please allow me to explain a little.

Siyah Kalem, which literally translates from Turkish as ‘Black Pen’, is the name given to a 14th century miniature painter and storyteller, who historians believe originated from around the Mongolian Steppe.

It is believed that Siyah Kalem also lived and worked along the Silk Road around the northern region of Persia and, that he earned his living by wandering from village to village busking with his artists scroll and stories.

I have to say here that I’ve been very cautious over the years not to learn too much about Siyah Kalem, especially the academic interpretation of his life and works. Fortunately, most are written in Turkish and been easy to ignore.

I’ve deliberately tried to remain as naive as possible. For me, looking at Siyah Kalem’s work was always about my imagination rather than digging for facts and I always felt that knowing too much would have tainted my response.

So, in the 15th Century Siyah Kalem’s scroll eventually found its way into the treasure collection of the Ottomans and then, in the 16th Century, it was cut up and placed in an album.

I know this seems like vandalism to us now, but books had become the fashion at that time and actually, the act of cutting up the scroll was probably what saved it from being lost forever. Because, as a result of this, the album they made was placed in the library at the Topkapi palace and survived.

One of the interesting things I found about the works of Siyah Kalem are the little marks one sees as one studies each plate; the odd pen mark or scribbled word; here and there the eyes are gouged out; and the grubby marks of a well-read book. In my imagination, I often visualise the Sultan’s children sitting in the Hareem at Topkapi Palace, mesmerised by its characters.

A Turkish friend in Istanbul once told me that as a child Siyah Kalem’s demons gave him terrible nightmares and it amused me greatly to think that Siyah Kalem could have been the Ottoman equivalent of Dr. Who, with generations of little princes and princesses hiding behind their Ottoman sofas in terror!

Which sort of brings us to the moment when we collided. Siyah kalem and I.

I actually first encountered Siyah Kalem myself in 2005 at the Royal Academy exhibition: ‘Turks, a journey of a thousand years’. Which was an exhibition of beautiful Turkish antiques and treasure, including the Palace of Topkapi and its library.

Nestled amongst the religious manuscripts and court documents of the Topkapi Palace library display, was the Siyah Kalem album. The pages had been teased apart so there were quite a few on display.

The encounter was magical, as Siyah Kalem’s work immediately stood out as different to the flattened-out illustrations in other books around it. His work was so idiosyncratic, his characters so full of life, they captivated my imagination.

My own fascination with Siyah Kalem began right there and then. Little did I know though, that that fascination would spark an incredible personal journey, and be driving force behind so many artists residencies and exhibitions in Turkey. Showing this work in the UK is a very proud moment for me.

So, in 2009. I attended my first artists’ residency in Istanbul, at Platform Garanti.

Right from the start I began to make a deeper connection to Siyah kalem by chatting about him with the Turkish artists in the other studios around me.

It turned out that Siyah Kalem had been adopted into the cultural psyche of Turkey, even playing a role in the education curriculum. I discovered his work had lived on and remained still relevant to so many people. My interest kept growing.

It was shortly after that that I chanced upon a copy of an old catalogue from a previous museum exhibition of Siyah Kalem’s work in a second-hand bookshop.

I’ve been wandering around with that same copy ever since.

It was through the pages of this book that I first began to see similarities between the people and situations of the past to those around me in contemporary Istanbul.

There was actually a moment in a street near the Grand Bazaar where I witnessed a man crouching in what Turks call, “the Anatolian seat”, a sort of squatting position. I knew I’d seen something similar in the book, so I took his photograph.

It was from this starting point that I began to get quite obsessed with seeking out similarities in the people and scenes around me and trying to capture them.

My first instincts toward this work were figurative and tended to be simple observations and quite objective. I spent a lot of time walking around photographing and sketching people, trying to work out my ideas.

In the end though, I couldn’t make it work. I think my lack of real understanding at the time of what Turkish culture was, made me always feel like an outsider. I was filled with doubt. I think I even felt a little voyeuristic.

So, I stopped making the work, but I didn’t give up the thought of one day picking it up again, and the ideas bubbled along behind everything else I made. It was around that time that I started learning more about Turkish culture and history. I also began to learn the Turkish language.

In 2016/17, at my studio in Sheffield, I started pottering around with ideas around materiality and my work with scale and model making started to translate into to something more metaphorical. I also started to work in concrete and clay, and something architectural and historical started to happen in the background of the things I was making.

It was from this that I began to see a new approach to Siyah Kalem and a new way of approaching the city.

It was also around this time that I started to realise that Siyah Kalem and I had something very much in common: That we were actually both outsiders.

It was this realisation that liberated me from my worst self-doubts and opened me to the idea of myself as more than just an observer, but as a nomad and a storyteller in a position to make my own narrative.

In 2018, with the help of a Making Ways grant, I returned to Istanbul, attending my first residency at Halka Art Projects.

Over the next few years, working in my little studio above their gallery, I made two new and distinct bodies of work from Siyah Kalem book, both of which resulted in Solo exhibitions there.

The first body of work I made and exhibited was titled ‘A Nomad’s Tale’ (Bir Göçebe Masalı), which dealt with the 37 social observational drawings in the first part of the Siyah Kalem catalogue.

This work was mostly sculptural and used textiles, models, castings, carving, rug-making, and some found objects. There were also some 2D works that appropriated graffiti tags and stencil motifs from the city walls around me.

The second exhibition, ‘The Devils Feather’ (Seytan Tuyu), which is a common Turkish phrase similar to our ‘The luck of the devil’, dealt with the remaining 15 Demons paintings. This dealt with something less tangible and more subjective. It touched on superstition, on the political; and as I previously mentioned, on the surfaces of the world around me.

It was through this work that my experiences of the political machinations of turkey, the fables people had shared with me, my travels, and my encounters, began to come together into the spirit of the work.

Which leads us up to this point and my exhibition Nomadic Tales, here at Millennium Gallery, Sheffield.

The title is meant to be a little ambiguous as to which nomad’s tale this is actually telling: Mine or Siyah Kalem’s.

Because, as I’m sure you already realise, we’re a little inseparable. The thread that ties us together is very strong, both in life and in this work.

The exhibition itself, is actually the two previous exhibitions, brought together into one single installation. With the demons hanging from the ceilings and walls, a little like the flags in a baronial hall, and the hand cart. Which is a scaled-up version of something from my ‘A Nomad’s Tale’ exhibition of 2018, sitting in the centre as a kind of witness to the scene around it.

Scale is very important here, and worth talking about briefly. One of the things that stood out to me as I looked at the catalogue 11 years ago, was how the author of the book had been so meticulous in recording the size of the original artworks.

I realised that each one of these surviving fragments was so important, down to the millimetre, and started play around with this in the work.

In 2009 this translated into making paper pieces identical in size to Siyah Kalem’s.

In 2018 these measurements became integral to the size and shape of many of the sculptures I was making.

In Seytan Tuyu, I wanted to work bigger than Siyah Kalem’s originals to allow me space to play with the paint more and to give the works more of a contemporary edge.

So, in that instance I actually changed the scale from metric to Imperial, 22.3cm became 22.3 inches and so on. Making the work almost three times larger.

Here, for this exhibition, I wanted something considerably more visually impacting, that I could work on with more physicality and, that would fill the gallery. So, I simply moved the decimal place over, turning 22.3cm into 223cm.

I’ll be resisting the urge to make a 223-inch version of this work though. Unless the authorities in Istanbul decide to give me a few gable-ends to paint.

I’m sure you’ve noticed that there are no titles to the individual pieces in the exhibition, this isn’t just because this is one installation work, it’s also because a title would be too leading. As I already mentioned, the work is about imagining a story.

So I’m not in the habit of describing the work. But I am aware that people want to know more. Especially here in the UK. In Turkey, many of the motifs and subjects matter I’ve used are very familiar and far more accessible, even a little troubling.

So, I will chat a bit about the work, and if there are any questions later, I will gladly go deeper.

As I mentioned before, much of the subject matter in this work is taken from the politics and stories from the streets around where I live in Istanbul.

For example, this one, which the author of the catalogue titled, ‘Demons playing music and having fun’, is one of my personal favourites. I like its simplicity.

Where I live, in Kadikoy on the Asian side of the Bosporus, it’s kind of an island, with the sea on three sides. The coast, which actually goes all the way to Gebze is a strip of reclaimed land, with a continuous cycle and running path about 26 miles long. With skate parks, and tennis and basketball courts, and football pitches, and concert venues and cafes, and beaches. Its always packed with people.

Between the sea and the land there is a long manmade strip of rocks that serves as a barrier, and In the evenings, and weekends, teenagers go down and sit on the rocks; they smoke joints, drink beer, play their guitars, court their girlfriends, and eat snacks – mostly nuts and sunflower seeds.

This work is a reflection on that youth culture, it takes the drunken musicians and characters of the original Siyah Kalem work and re-presents them as that youth culture with its seeds, and it tattoos, and beat.

© Richard Bartle, all rights reserved.